By Glenn Murray on Jun 9, 2020 10:30:00 AM

The topic of bias, especially the area of cognitive bias, has garnered quite a lot of attention by safety professionals in recent years. Cognitive bias can, for example, strongly influence decision making by leaders and managers whose roles include budgeting and staffing decisions, among many others, both of which can have potentially significant safety-related consequences, most often unintended consequences.

But what about this thing called Visual bias?

Let’s begin with a couple of key underlying Visual Literacy concepts. The first relates to the model of Speaking Visual Language, illustrated by the graphic below.

Speaking Visual Language

If you follow the triangle from the upper left and move counterclockwise, the model moves us from merely looking at an image (or scenario), to observing it, and then to actually seeing it. But the process doesn’t stop there. Once we truly see something, then we are better able to effectively interpret its meaning, which ultimately informs our actions.

If you follow the triangle from the upper left and move counterclockwise, the model moves us from merely looking at an image (or scenario), to observing it, and then to actually seeing it. But the process doesn’t stop there. Once we truly see something, then we are better able to effectively interpret its meaning, which ultimately informs our actions.

The second key concept is the fact that we don’t actually see with our eyes. We see with our brains. Our brains send signals to our eyes that govern where to look, how to look at it, how long to look at it, what to look for, etc.

Therefore, seeing is essentially a cognitive process. And through practice, we can improve our seeing skills. In fact, there are tools and techniques that can be learned and employed to help us see more effectively.

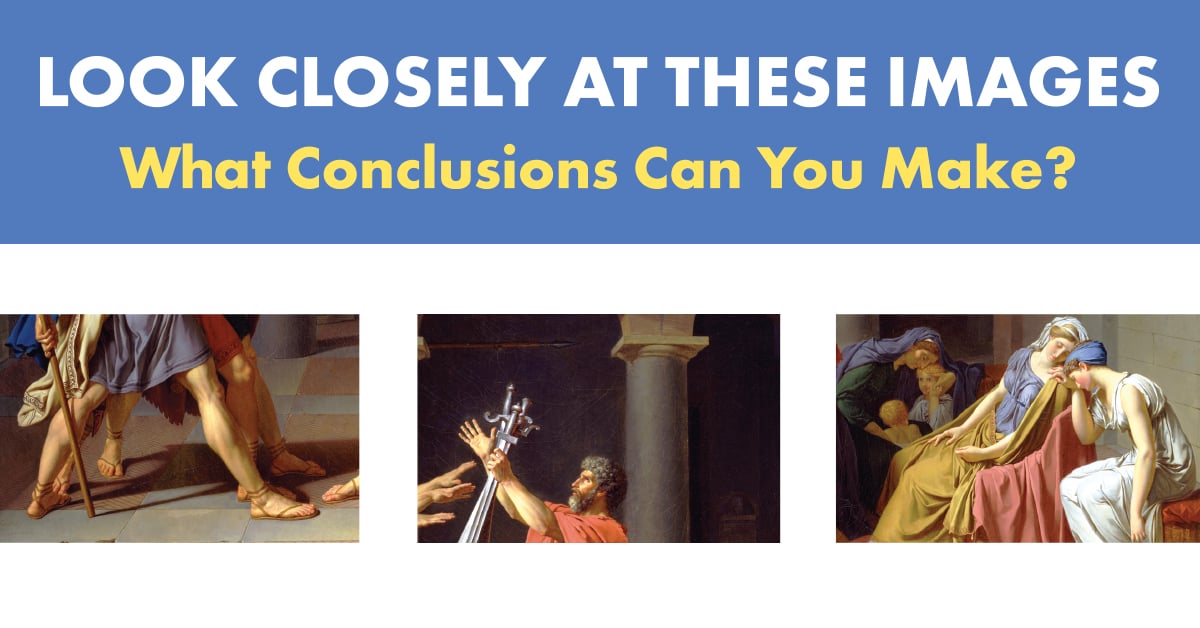

Consider a relatively common workplace scenario:

You are the Safety Advisor at an operating site. You, several first line supervisors, and the Site Manager are conducting a weekly ‘safety walk-around’ at the site. It is the Manager’s first assignment at a site like this one. During your walk, the group stops to observe a unit that is under construction. The unit is surrounded by scaffolding. There are workers on the scaffolding and around the equipment performing various construction activities.

At the end of the walk-around, the group meets back in the Manager’s office to discuss their observations and to compare notes. They had all ‘looked at’ and ‘observed’ the very same things. But not surprisingly, they all saw some very different things, and in some cases didn’t see some things at all. And as such, their interpretations of what they saw, and their sense for what actions would be appropriate were likely not the same.

How can this happen? It will almost always happen, because what they saw, how they saw it, and how they interpreted its meaning were strongly influenced by their life experiences, their areas of expertise, their backgrounds, their training, etc. — because they have biases. Hopefully, you can imagine many other scenarios where visual bias can play a potentially significant role, such as with hazard recognition, risk assessment, Serious Injury & Fatality potential determination, incident investigation, etc.

Biases are not necessarily ‘bad’ things. We all have biases. It’s human nature to have biases. And as we all know, it isn’t easy to ‘change’ biases, since some of them are based on deep-seated experiences and influences in our lives. But what is important is to be aware of biases, to understand what they are, to acknowledge how they can influence the way we think and the way we see – and if necessary, take steps to compensate for or address biases.

One way to compensate for bias is through ensuring that work teams, project teams, observation teams and the like are made up of individuals with diverse backgrounds, experience, and expertise.

Another important way to address bias is to provide structured, disciplined, systemic approaches that help to ensure greater objectivity and more effective critical thinking.

COVE | Center of Visual Expertise offers such a suite of tools and skills - specifically designed to help with Visual Bias - such as the Elements of Art, Speaking Visual Language, and Seeing the Whole PICTURE®, all of which can help managers, supervisors, and workers more effectively see what they are looking at - see in a more deliberate, systemic, purposeful way.

For additional insight into this approach, download our ebook Identifying Hazards In The Workplace: A New Approach That Starts With Seeing.